Iwane Nursery Schools

- At July 27, 2016

- By anneblog

- In Annes Letters

0

0

Dear Family and Friends,

In a previous essay I told you about Iwate Prefecture and several remarkable people there.This time I would like to introduce work being done in that area by Caritas Switzerland. There were other groups involved in these projects, too: Taiwan Red Cross through the Japanese Red Cross (for the Kirikiri Nursery), the Swiss Red Cross through Caritas Switzerland, Swiss Solidarity, and Catholic Relief Services, which is the American Caritas. But the woman I went with is involved with Caritas Switzerland, so that is where my focus will be.

As you probably know, Caritas Internationalis is a Roman Catholic organization devoted to “relief, development, and social service work”. This confederation has 165 branches, making it one of the largest humanitarian networks in the world. Its main headquarters are in Vatican City. Although it is Roman Catholic based, it does not proselytize or deny assistance because of religious belief. Each of the 165 branches works under the large umbrella of Caritas Internationalis, but is independent of the others. For example, Caritas Japan has a different agenda in Tohoku from Caritas Switzerland. Although both are doing work in the same areas, they do not interfere with one another. To be specific, on this Tohoku project, which is a one-time relief service, Caritas Switzerland mainly concerns itself with physical rebuilding, whereas Caritas Japan focuses mainly on the emotional well being of 03/11 survivors.

A former student, now friend, Akiko Wako, works for Caritas Switzerland in Iwate. Because of my interest in what is happening in Tohoku, she agreed to escort me to Kawaishi City, where she has been heavily involved in rebuilding the four nursery schools under Caritas Switzerland’s wing.

As we came to the city, we were met by an ongoing parade of trucks and clusters of backhoes. They were literally raising the level of ground that the coastal communities will stand on.

We also saw signs all along the hilly main road indicating how far the tsunami had come. So, the atmosphere was one of great busy-ness and of renewal. It felt hopeful.

Caritas Switzerland decided to focus its work on rebuilding four nursery schools. Why, you might think, would they put their effort into those places, when so much other fundamental work seemed more pressing? One answer is that Caritas Switzerland, like Japan in general, thinks long term. If children have good care, they reason, then young families will be more likely to stay. And indeed, the drain of people from coastal areas has been alarming. Likewise, if formative years are secure and love-filled, then children will have a greater chance of having secure lives. And in the long term, that will make for a more stable society.

(photo copyright Caritas Switzerland, used with permission)

The first nursery school we visited was in Unosumai-cho district of Kamaishi City. It was gorgeous. It had a long wooden corridor with brightly lit rooms, one for each age, off each side. There were windows everywhere, not only for light to enter, but also to allow the youngsters to peer into places like the kitchen or the main playroom.

The building also had skylights on the roof, plus solar and wind power devices. There was a digital chart showing how the natural energy was being used. It also had well water for the garden and for use in emergencies. And there was a vegetable garden that produced fresh food for the school’s meals. It also gave the children a chance to get their hands in the earth and to be part of the life-giving process of farming.

The building adjacent to the main nursery served as an evacuation center. In Japan schools are used by the entire community in times of emergency. Likewise, this particular school hosted community events throughout the year. And one room was open to the public from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily so any child up to age 6 could come and play, as long as they were accompanied by an adult.

The school itself was not only physically stunning. It was also very welcoming and warm. For example, when we arrived, there were a few bags of vegetables that parents had brought as an offering. And the walls were covered with children’s work.

The ratio of teachers to youngsters was very low: about 1 to 3. As for the infants, there were 4 teachers for the 9 babies.

Before this facility was open, this nursery cared for its children in a community center. Other nursery schools were housed in buildings provided by UNICEF or by the Japanese government. The community really cares about the future of its children. And the efforts it now makes on its youngsters’ behalf will surely bear fruit in the years to come.

The second place we visited was called Kirikiri Nursery. It was in the Otsuchi-cho district of Kamaishi City. Since it was built on an exceedingly slim edge of newly leveled land, it had two storeys instead of only one. It also had what looked like a veranda on both sides of the building. They were actually easily accessible escape routes for times of emergency.

Upstairs was a large playroom. It had an inviting structure for climbing. “Kids started getting fat when they were trapped in evacuation centers and temporary housing,” our guide told us. “So, this is to encourage them to move their bodies as they should: to run and jump, to climb and play.”

The gentleman who followed along as we toured Kirikiri Nursery was Touemon Azumaya San. He was a jolly 81-year-old man who oversaw this nursery.

After our tour of the facility, he pointed out where the old school had stood for about 50 years. He also indicated where their temporary headquarters had been until a few months ago. And he even showed us the garden on his relative’s property where he grew vegetables for the school lunches.

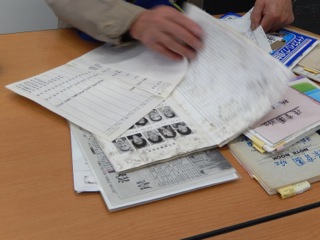

When we sat down for tea after our tour, Azumaya San brought out hand-written records he had methodically kept for years. Miraculously they had survived the tsunami. He whipped through every page, explaining his detailed notes: what days had been sunny, what had been served for meals, which teachers had been ill.

When he realized our genuine interest, he loosened up and began telling stories further afield. He talked of the war. (He was 10 then). He confessed that he had never finished school, but had gone north to Hokkaido to find work. He told us about the various jobs he had had, how he came back to Kamaishi, married and raised a family. He showed us a photo of his taisho koto musical group. And seemingly in passing, he said, “ This is the last photo taken of my wife and me together. She drowned in the tsunami.” No one in the room had known about his wife. Everyone was speechless, to say the least. Such stoic silence is the nature of Tohoku people. “We don’t want to bother people with our problems,” they explain.

But then his story seamlessly continued. “I love these kids.”

(photo copyright Caritas Switzerland, used with permission)

“We have to give them the best we can. How else can we create the future that we wish for them? And for the world as a whole as well?”

Love,

Anne