Arahama, 11 Months Later

- At July 26, 2016

- By anneblog

- In Annes Letters

0

0

Mid-February 2012

Dear Family and Friends,

Recently a friend and I went north of Sendai to Kesennuma to learn firsthand how things were almost one year after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. This week different friends and I ventured closer to home to hear stories of people who used to have homes and work near the sea. We went to Arahama, one section of widely spread out Sendai City. We talked with four courageous souls. Each person had a story. Each tale was unique. But the underlying theme was the same: “We lost everything. The future is uncertain. We can only do what we can today.”

The four people we spoke to all came from the same area within Arahama. One had been a farmer; one used to have a company making iron products; another had had a coffee shop; and one had been and still was a fisherwoman. We met in a restaurant that one of their friends, who also had lost everything, had recently opened.

Many people, locally, nationally, and internationally, were so profoundly moved by the terrible tragedy of March 11, 2011 that they felt a strong desire to help survivors. That is how this restaurant owner got started. Several people had given him rather generous monetary gifts, so he was able to open his establishment. The place was simple, tasteful and the food was delicious. On the walls hung huge banners that fishermen use here to signal their return home from a day – or longer – out at sea. They were colorful and bright, and lent an upbeat feel to the place. The man said he was doing what he had to survive, but he would always be a fisherman at heart. Someday, he hoped, he would be able to return to the sea and make his living there once again.

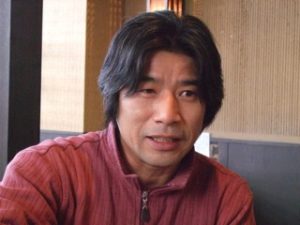

The first man of the four to tell his story was Kiichi Kida San. He was a proud farmer.

“My family has lived in Arahama for seventeen generations. We came here from the south in the days of Masamune Date when he was building the city of Sendai. He needed workers, so sent a plea out for people all over the country to come to Miyagi. That is how my family got here. Seventeen generations: that is about 400 years, you know. So my roots here are long and deep. And of course, no matter what, we plan to stay.”

Before the tsunami devastated his land, Kida San had grown vegetables. He and his wife had had their own pickle company. They used their own produce to make their well-known pickles. Their establishment was small, but successful. “But I’m in my late 60s now, so starting again seems rather daunting. There is glass and other bits of rubbish imbedded in the fields now. Cleaning that up will take forever. I would have kept on working much longer, but I’m not so sure now.

“I do know that I want to go back to my own land, however. My family roots there run very deep. The place calls me. I’m just waiting for the time when I can go back.”

The next man, Seiji Yamamoto San, was a plump, humorous fellow. His job just prior to the tsunami had involved iron. He and his son would build buildings of all sorts, bridges, and fences. “Anything to do with iron, we were happy to make,” he said.

“In junior high school I apprenticed to a barber. I’m sure that job would have been great, but the sensei and I fought all the time. So, I soon left. From there I did one job after another, always using my hands. Don’t ask me to write; I’m terrible at it. But ask me to make something with my hands, and I’m off and running.”

Yamamoto San was in his 70s, but the son who had worked with him in the iron company was only 25. The machines they had used in their business had been huge and extremely expensive. The tsunami took them in its grip, twisted, turned, and shook them up. “They are useless now. So, what am I going to do? I hate to buy others and put my son in debt for the rest of his life. He has only part-time work now. It doesn’t pay much. We are sort of in an interim trying to sort out what to do next.”

The next fellow had been a coffee shop owner. His name was Masato Sato San and he was the youngest of the group.

His shop had been far from the tsunami area, but he had lived with his family in Arahama. Sadly he had lost his home and his father in the tsunami. When he had his shop, he had commuted quite far from Arahama in the south to his shop in Izumi ward in the north. After the disaster, though, he decided to close his coffee shop and to return to Arahama to help the community there. Now he, like the others, lives in a temporary house and is waiting to see what will happen next.

“We are all waiting on the government. What really frustrates us is that the government officials – all with good intentions, I am sure – sit in offices and make plans for our neighborhood. They draw lines on maps. They never come and ask us anything. We are locals. We have lived here for generations. We know the land. We have your needs and ideas. We want the government to listen to us and to work with us. That way together we can come up with ideas on how best to rebuild our shattered community.

“Actually a whole group of us, 50 families in all, have joined together to make a group to rebuild our area. The group’s name is: Arahama no Saisei no Negau Kai. (Arahama’s Hope for Recovery Group.) Of course, the word ‘negau’ implies humbly asking. That could be to the gods, or to each other, or to government officials. We really are humbling asking those important people to work with us and not only for us.

“You see, the government is thinking of physical safety exclusively. That is important, of course. But we love this land. And we know that mental and emotional recovery is equally as important, if not more so, than physical safety. Because of our strong emotional attachment to the land that we lived on for generations, we are willing to take risks and go back. Of course, there will be other tsunami. We all know that. Hopefully they won’t be as bad as the last one. But no matter what, we want to go back to our land.”

The other Sato San, Yuko, the fisherwoman, also had quite a tale to tell.

Her family had been one of twelve in the area to collect small red shellfish, “Akakai”. The Arahama area has the best beds in Japan for this sort of shellfish, so their catch is always sent directly to Tokyo. Her family had owned two boats, which she and her parents operated. But the tsunami ploughed in and carried them off. One was carried out as far as Hawaiian waters, where it was deliberately sunk because it and the other masses of debris were getting in the way of ships. But miraculously their other boat was found and could be salvaged. It cost a fortune to clean and repair the engines, but the family realized the importance of taking that crucial step.

Now there are a total of only two boats working the Arahama beds, which astonishingly survived the tsunami. “But now the work is so much harder. We pull up more rubbish than shellfish, so we have to spend a long time cleaning everything. Then we take our catch to the university, where they check it for radiation levels. We have to pay for that, of course. All this is hard work, but we do it. It is our life. It is our blood. It is our survival.”

Later Yuko Sato San drove us to the site of her former community. We passed vast areas of emptiness, filled only with the base of houses. In some there were yellow prayer flags flapping in the breeze. People had written their prayers and wishes on those signs of hope. And everyone is indeed living with a sense of both waiting and of hope. The future is a vast unknown, but these folks firmly believe they can remake their lives and that someday, maybe ten years down the line, Arahama will become a viable community again.

I had been in Arahama one month after the tsunami so was impressed by how much had been cleared away. But the work of rebuilding had not yet begun and would not for several more years. Now it is basically an expansive empty space filled with concrete blocks outlining where homes used to stand.

Just after the tsunami

Now

The tall buildings of Sendai City center in the distance seemed dreamlike and strange. So close and yet another world completely.

Yuko Sato San was single and lived with her parents and grandmother. She told us that her grandmother had been “frail” before the tsunami, but after it she had become completely senile. She wandered around, totally disoriented. She moaned a lot. So, the family would drive her out to where their home had once stood. She would then settle down, walk around and seemed to be more her old self again.

The Sato family had made a teeny garden covered in plastic in what had been their living room. “It is hopeful for us,” she said. “Having a garden on our own land soothes our troubled hearts.”

As we pulled up to where their house had once stood, we saw her father sitting in the base of a house across from his own ruined home. He was fixing his fishing nets. “I come here to work. There is nothing here. But I work best in my own place.”

His daughter explained again, “We live with the essence of our ancestors here. They permeate this land. How can any government official ask us to leave here forever? How could they not understand?”

Love, Anne